|

The most frequent cause of thyroid enlargement in children and adolescents is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. This is more common in girls and in those with a family history of Hashimoto’s or other thyroid disorders. Apart from the enlarged thyroid, there may be no other changes unless hypothyroidism develops. The management of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children and adolescents is exactly the same as in adults. Over time, the thyroid will become smaller but this may take several years. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, thyroid hormone secretion may be normal at diagnosis, but monitoring is recommended in case hypothyroidism develops. Treatment with thyroid hormone, once started, is taken for life. There are special groups of children, such as those with Diabetes Mellitus type 1, Down Syndrome, or Turner Syndrome, who should be regularly checked, as they are more likely to develop Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

|

|

Hashimoto's Thyroiditis

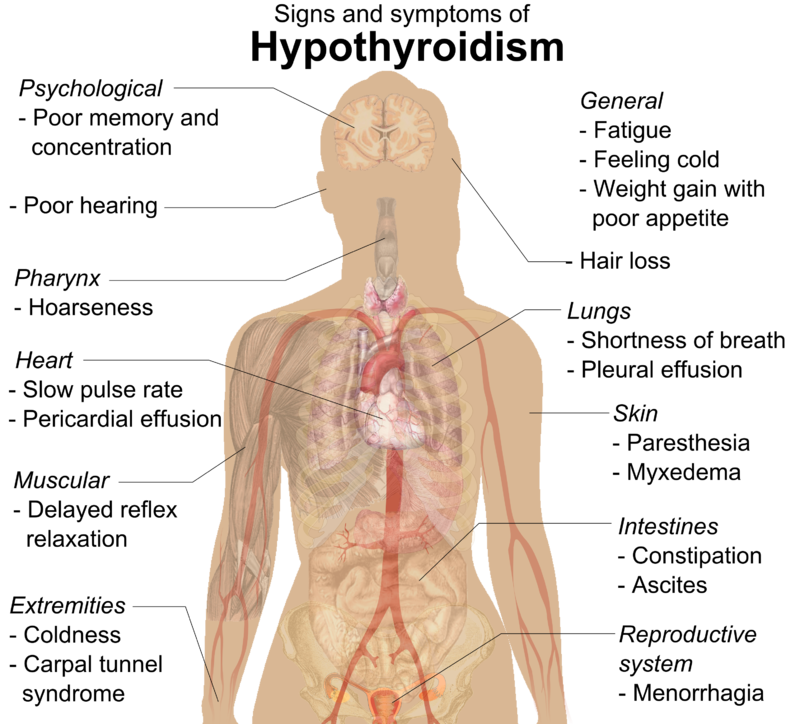

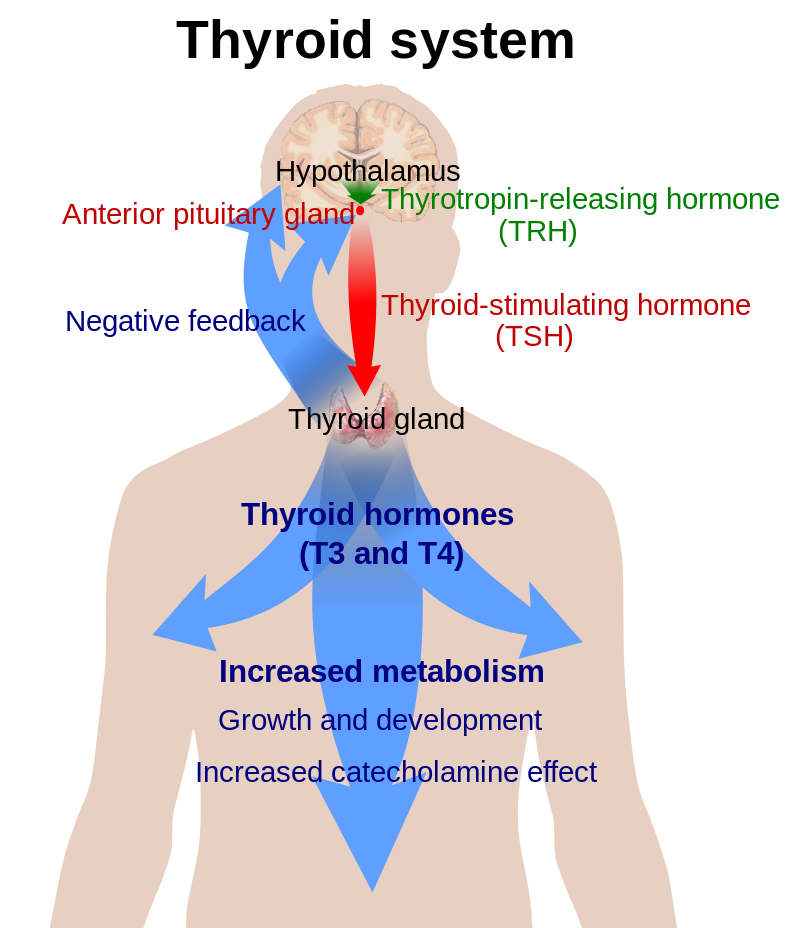

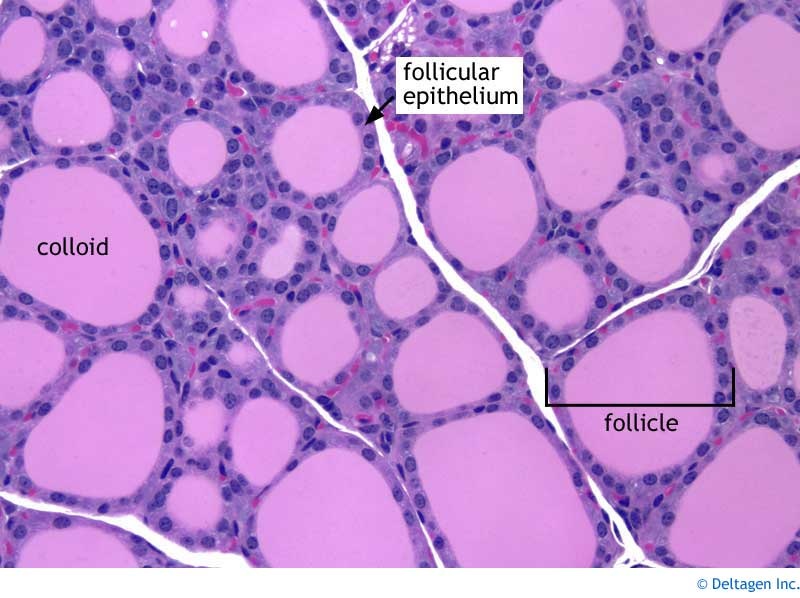

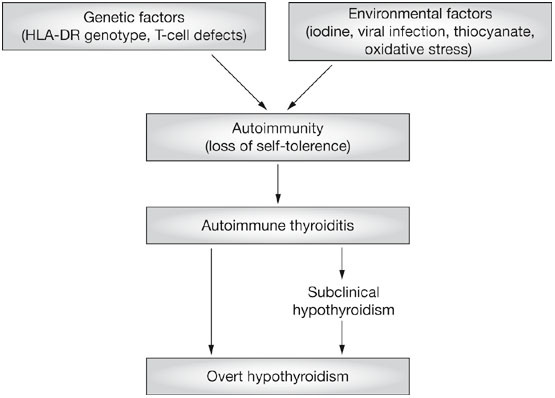

Thyroiditis, or inflammation of the thyroid gland, has many causes. The most common cause is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, first described by Dr Hashimoto in Japan. This is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the thyroid gland caused by abnormal blood antibodies and white blood cells attacking and damaging thyroid cells. The end result of this so-called "autoimmune" destruction is hypothyroidism or underactive thyroid functioning. Some patients are able to retain sufficient thyroid reserve to prevent hypothyroidism. Clinical Features Patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are usually, young, middle-aged or older women. They often have no symptoms apart from mild pressure in the thyroid gland and tiredness. In the early stages there is a goitre which is firm, slightly irregular, and sometimes slightly tender. Pain occurs in about 10% of cases. In the later stages the thyroid can become small and non palpable. Laboratory Tests The diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is confirmed by finding high levels of antibodies in the blood. These work against the patient’s own thyroid proteins. The diagnosis can be firmly established by doing a thyroid biopsy but this is not usually done. To determine the function of the gland the level of TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) is measured in the blood. TSH is the pituitary signal that controls thyroid function and growth (please refer to health guide 2). Women over 50 years of age should be periodically screened for thyroid dysfunction. Treatment Treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis consists of replacing the missing thyroid hormone, thyroxine. This is accomplished by taking a pill containing thyroxine (Euthyrox®, Synthroid®, Eltroxin®). If the dysfunction is mild, doses of 50 to 75 micrograms per day may be sufficient. The average replacement dose for more severe dysfunction is 1.6 micrograms/kg of body weight. If patients present with hypothyroidism and goitre, the goitre will usually shrink 6 to 18 months after replacement therapy has been introduced. Once the proper dose of thyroxine has been established, patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis should be seen by their family doctors at least once a year to ensure that the dose of thyroxine is still adequate. |

J Pediatr. 2016 Mar;170:253-9.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.008. Epub 2015 Dec 17.

Pediatric Goiter: Can Thyroid Disorders Be Predicted at Diagnosis and in Follow-Up?

Kim SY1, Lee YA1, Jung HW1, Kim HY2, Lee HJ1, Shin CH1, Yang SW1.Author information

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:To investigate the prevalence of thyroid dysfunction, autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), and simple goiter at goiter diagnosis, and to analyze the natural course of simple goiter and predictors for progression to AITD and/or thyroid dysfunction.

STUDY DESIGN:In total, 939 patients (770 females, 5.0-17.9 years) with goiter were reviewed retrospectively. Anthropometrics, pubertal status, goiter grade, and family history (FH) of thyroid disease were investigated. Simple goiter was defined as euthyroid goiter without pathologic cause, after excluding AITD and isolated nonautoimmune hyperthyrotropinemia (iso-NAHT).

RESULTS:At diagnosis, 36.9% of children showed thyroid dysfunction and/or AITD (euthyroid AITD [9.9%], hyper- or hypothyroid AITD [18.4%], iso-NAHT [8.6%]). Risk for subsequent medication was higher in euthyroid AITD than simple goiter (20.4% vs 0.3%, P < .001). Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) and iso-NAHT developed in 5.2% and 6.6% of patients initially diagnosed with simple goiter during the median 2.0-year follow-up. Compared with the persistent simple goiter group, the HT group had greater FH (54.8% vs 23.6%) and unchanged or increasing goiter size (89.3% vs 71.8%), and the iso-NAHT group had a higher proportion of patients within the upper tertile range of baseline thyrotropin levels (71.8% vs 24.9%) and unchanged or increasing goiter size (86.8% vs 71.8%; all P < .05).

CONCLUSIONS:Thyroid disorders were detected in one-third of pediatric patients presenting with goiter. The higher risk for thyroiddysfunction needing medication in patients with euthyroid AITD emphasizes the importance of autoantibody evaluation at diagnosis. During simple goiter follow-up, progression to HT or iso-NAHT occurs, especially in patients with FH or persistent goiter.